Cerebral palsy

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Cerebral palsy |

|---|

|

| A child with cerebral palsy |

| Specialty | Pediatrics, neurology, physiatry |

|---|

| Symptoms | Poor coordination, stiff muscles, weak muscles, tremors |

|---|

| Complications | Seizures, intellectual disability |

|---|

| Usual onset | Early childhood |

|---|

| Duration | Lifelong |

|---|

| Causes | Often unknown |

|---|

| Risk factors | Preterm birth, being a twin, certain infections during pregnancy, difficult delivery |

|---|

| Diagnostic method | Based on child's development |

|---|

| Treatment | Physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, external braces, orthopedic surgery |

|---|

| Medication | Diazepam, baclofen, botulinum toxin |

|---|

| Frequency | 2.1 per 1,000 | | | | | | | | | |

|---|

Cerebral palsy (

CP) is a group of permanent movement disorders that appear in early childhood. Signs and symptoms vary among people and over time. Often, symptoms include poor coordination, stiff muscles, weak muscles, and tremors. There may be problems with sensation, vision, hearing, swallowing, and speaking. Often, babies with cerebral palsy do not roll over, sit, crawl or walk as early as other children of their age. Other symptoms include seizures and problems with thinking or reasoning, which each occur in about one third of people with CP. While symptoms may get more noticeable over the first few years of life, underlying problems do not worsen over time.

Cerebral palsy is caused by abnormal development or damage to the

parts of the brain that control movement, balance, and posture. Most often, the problems occur during pregnancy; however, they may also occur during childbirth or shortly after birth. Often, the cause is unknown. Risk factors include preterm birth, being a twin, certain infections during pregnancy such as toxoplasmosis or rubella, exposure to methylmercury during pregnancy, a difficult delivery, and head trauma during the first few years of life, among others. About 2% of cases are believed to be due to an inherited genetic cause. A number of sub-types are classified based on the specific problems present. For example, those with stiff muscles have spastic cerebral palsy, those with poor coordination have ataxic cerebral palsy and those with writhing movements have athetoid cerebral palsy. Diagnosis is based on the child's development over time. Blood tests and medical imaging may be used to rule out other possible causes.

CP is partly preventable through immunization of the mother and

efforts to prevent head injuries in children such as through improved

safety. There is no cure for CP; however, supportive treatments, medications and surgery may help many individuals. This may include physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. Medications such as diazepam, baclofen and botulinum toxin may help relax stiff muscles. Surgery may include lengthening muscles and cutting overly active nerves. Often, external braces and other assistive technology are helpful. Some affected children can achieve near normal adult lives with appropriate treatment. While alternative medicines are frequently used, there is no evidence to support their use.

Cerebral palsy is the most common movement disorder in children. It occurs in about 2.1 per 1,000 live births. Cerebral palsy has been documented throughout history, with the first known descriptions occurring in the work of Hippocrates in the 5th century BCE. Extensive study of the condition began in the 19th century by William John Little, after whom spastic diplegia was called "Little's disease".

William Osler first named it "cerebral palsy" from the German

zerebrale Kinderlähmung (cerebral child-paralysis).

A number of potential treatments are being examined, including stem cell therapy. However, more research is required to determine if it is effective and safe.

Signs and symptoms

Cerebral palsy is defined as "a group of permanent disorders of the

development of movement and posture, causing activity limitation, that

are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occurred in the

developing fetal or infant brain."

While movement problems are the central feature of CP, difficulties

with thinking, learning, feeling, communication and behavior often

co-occur,

with 28% having epilepsy, 58% having difficulties with communication,

at least 42% having problems with their vision, and 23–56% having

learning disabilities. Muscle contractions in people with cerebral palsy are commonly thought to arise from overactivation.

Cerebral palsy is characterized by abnormal muscle tone,

reflexes, or motor development and coordination. The neurological

lesion is primary and permanent while orthopedic manifestations are

secondary and progressive. In cerebral palsy unequal growth between

muscle-tendon units and bone eventually leads to bone and joint

deformities. At first deformities are dynamic. Over time, deformities

tend to become static, and joint contractures develop. Deformities in

general and static deformities in specific (joint contractures)

cause increasing gait difficulties in the form of tip-toeing gait, due

to tightness of the Achilles tendon, and scissoring gait, due to

tightness of the hip adductors. These gait patterns are among the most

common gait abnormalities in children with cerebral palsy. However,

orthopaedic manifestations of cerebral palsy are diverse.

The effects of cerebral palsy fall on a continuum of motor dysfunction,

which may range from slight clumsiness at the mild end of the spectrum

to impairments so severe that they render coordinated movement virtually

impossible at the other end of the spectrum.

[citation needed]

Although most people with CP have problems with increased muscle tone,

some have normal or low muscle tone. High muscle tone can either be due

to spasticity or dystonia.

Babies born with severe cerebral palsy often have an irregular

posture; their bodies may be either very floppy or very stiff. Birth

defects, such as spinal curvature, a small jawbone, or a small head

sometimes occur along with CP. Symptoms may appear or change as a child

gets older. Babies born with cerebral palsy do not immediately present

with symptoms.

Classically, CP becomes evident when the baby reaches the developmental

stage at 6 to 9 months and is starting to mobilise, where preferential

use of limbs, asymmetry, or gross motor developmental delay is seen.

Drooling is common among children with cerebral palsy, which can

have a variety of impacts including social rejection, impaired speaking,

damage to clothing and books, and mouth infections. It can additionally cause choking.

An average of 55.5% of people with cerebral palsy experience lower urinary tract symptoms, more commonly excessive storage issues than voiding issues. Those with voiding issues and pelvic floor overactivity can deteriorate as adults and experience upper urinary tract dysfunction.

Children with CP may also have sensory processing issues. Adults with cerebral palsy have a higher risk of respiratory failur.

Skeleton

For bones to attain their normal shape and size, they require the stresses from normal musculature. People with cerebral palsy are at risk of low bone mineral density. The shafts of the bones are often thin (gracile), and become thinner during growth. When compared to these thin shafts (diaphyses), the centres (metaphyses) often appear quite enlarged (ballooning).

[citation needed] Due to more than normal joint compression caused by muscular imbalances, articular cartilage may atrophy

:46

leading to narrowed joint spaces. Depending on the degree of

spasticity, a person with CP may exhibit a variety of angular joint

deformities. Because vertebral bodies need vertical gravitational

loading forces to develop properly, spasticity and an abnormal gait can

hinder proper or full bone and skeletal development. People with CP tend

to be shorter in height than the average person because their bones are

not allowed to grow to their full potential. Sometimes bones grow to

different lengths, so the person may have one leg longer than the other.

[citation needed]

Children with CP are prone to low trauma fractures, particularly children with higher GMFCS

levels who cannot walk. This further affects a child's mobility,

strength, experience of pain, and can lead to missed schooling or child

abuse suspicions.

These children generally have fractures in the legs, whereas

non-affected children mostly fracture their arms in the context of

sporting activities.

Hip dislocation and ankle equinus or planter flexion deformity

are the two most common deformities among children with cerebral palsy.

Additionally, flexion deformity of the hip and knee can occur. Besides,

torsional deformities of long bones such as the femur and tibia are

encountered among others. Children may develop scoliosis before the age of 10 – estimated prevalence of scoliosis in children with CP is between 21% and 64%. Higher levels of impairment on the GMFCS are associated with scoliosis and hip dislocation. Scoliosis can be corrected with surgery, but CP makes surgical complications more likely, even with improved techniques.

Hip migration can be managed by soft tissue procedures such as adductor

musculature release. Advanced degrees of hip migration or dislocation

can be managed by more extensive procedures such as femoral and pelvic

corrective osteotomies. Both soft tissue and bony procedures aim at

prevention of hip dislocation in the early phases or aim at hip

containment and restoration of anatomy in the late phases of disease.

Equinus deformity is managed by conservative methods especially when

dynamic. If fixed/static deformity ensues surgery may become mandatory.

Growth spurts during puberty can make walking more difficult.

Eating

Due to

sensory and motor impairments, those with CP may have difficulty

preparing food, holding utensils, or chewing and swallowing. An infant

with CP may not be able to suck, swallow or chew. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is common in children with CP. Children with CP may have too little or too much sensitivity around and in the mouth.

Poor balance when sitting, lack of control of the head, mouth and

trunk, not being able to bend the hips enough to allow the arms to

stretch forward to reach and grasp food or utensils, and lack of hand-eye coordination can make self-feeding difficult. Feeding difficulties are related to higher GMFCS levels. Dental problems can also contribute to difficulties with eating. Pneumonia is also common where eating difficulties exist, caused by undetected aspiration of food or liquids.

Fine finger dexterity, like that needed for picking up a utensil, is

more frequently impaired than gross manual dexterity, like that needed

for spooning food onto a plate.

[non-primary source needed] Grip strength impairments are less common.

[non-primary source needed]

Children with severe cerebral palsy, particularly with oropharyngeal issues, are at risk of undernutrition. Triceps skin fold tests have been found to be a very reliable indicator of malnutrition in children with cerebral palsy.

Language

Speech and language disorders are common in people with cerebral palsy. The incidence of dysarthria is estimated to range from 31% to 88%, and around a quarter of people with CP are non-verbal. Speech problems are associated with poor respiratory control, laryngeal and velopharyngeal dysfunction, and oral articulation

disorders that are due to restricted movement in the oral-facial

muscles. There are three major types of dysarthria in cerebral palsy:

spastic, dyskinetic (athetosis), and ataxic.

Early use of augmentative and alternative communication systems may assist the child in developing spoken language skills. Overall language delay is associated with problems of cognition, deafness, and learned helplessness.

Children with cerebral palsy are at risk of learned helplessness and

becoming passive communicators, initiating little communication.

Early intervention with this clientele, and their parents, often

targets situations in which children communicate with others so that

they learn that they can control people and objects in their environment

through this communication, including making choices, decisions, and

mistakes.

Pain and sleep

Pain

is common and may result from the inherent deficits associated with the

condition, along with the numerous procedures children typically face. When children with cerebral palsy are in pain, they experience worse muscle spasms.

Pain is associated with tight or shortened muscles, abnormal posture,

stiff joints, unsuitable orthosis, etc. Hip migration or dislocation is a

recognizable source of pain in CP children and especially in the

adolescent population. Nevertheless, the adequate scoring and scaling of

pain in CP children remains challenging. Pain in CP has a number of different causes, and different pains respond to different treatments.

There is also a high likelihood of chronic sleep disorders secondary to both physical and environmental factors. Children with cerebral palsy have significantly higher rates of sleep disturbance than typically developing children.

Babies with cerebral palsy who have stiffness issues might cry more and

be harder to put to sleep than non-disabled babies, or "floppy" babies

might be lethargic. Chronic pain is under-recognized in children with cerebral palsy, even though 3 out of 4 children with cerebral palsy experience pain.

Associated disorders

Associated disorders include intellectual disabilities, seizures, muscle contractures, abnormal gait, osteoporosis, communication disorders, malnutrition, sleep disorders, and mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety. In addition to these, functional gastrointestinal abnormalities contributing to bowel obstruction, vomiting, and constipation

may also arise. Adults with cerebral palsy may have ischemic heart

disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer, and trauma more often. Obesity in people with cerebral palsy or a more severe Gross Motor Function Classification System assessment in particular are considered risk factors for multimorbidity. Other medical issues can be mistaken for being symptoms of cerebral palsy, and so may not be treated correctly.

Related conditions can include apraxia, dysarthria or other communication disorders, sensory impairments, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, or behavioural disorders.

[citation needed]

Seizure management is more difficult in people with CP as seizures often last longer.

The associated disorders that co-occur with cerebral palsy may be more disabling than the motor function problems.

Causes

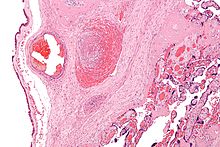

Micrograph showing a fetal (placental) vein thrombosis, in a case of fetal thrombotic vasculopathy. This is associated with cerebral palsy and is suggestive of a hypercoagulable state as the underlying cause.

Cerebral palsy is due to abnormal development or damage occurring to the developing brain. This damage can occur during pregnancy, delivery, the first month of life, or less commonly in early childhood. Structural problems in the brain are seen in 80% of cases, most commonly within the white matter.

More than three-quarters of cases are believed to result from issues that occur during pregnancy. Most children who are born with cerebral palsy have more than one risk factor associated with CP.

While in certain cases there is no identifiable cause, typical

causes include problems in intrauterine development (e.g. exposure to

radiation, infection, fetal growth restriction), hypoxia

of the brain (thrombotic events, placental conditions), birth trauma

during labor and delivery, and complications around birth or during

childhood.

In Africa birth asphyxia, high bilirubin levels,

and infections in newborns of the central nervous system are main

cause. Many cases of CP in Africa could be prevented with better

resources available.

Preterm birth

Between 40% and 50% of all children who develop cerebral palsy were born prematurely. Most of these cases (75-90%) are believed due to issues that occur around the time of birth, often just after birth. Multiple-birth infants are also more likely than single-birth infants to have CP. They are also more likely to be born with a low birth weight.

In those who are born with a weight between 1 kg and 1.5 kg CP occurs in 6%. Among those born before 28 weeks of gestation it occurs in 11%. Genetic factors are believed to play an important role in prematurity and cerebral palsy generally. While in those who are born between 34 and 37 weeks the risk is 0.4% (three times normal).

Term infants

In babies that are born at term risk factors include problems with the placenta, birth defects, low birth weight, breathing meconium into the lungs, a delivery requiring either the use of instruments or an emergency Caesarean section, birth asphyxia, seizures just after birth, respiratory distress syndrome, low blood sugar, and infections in the baby.

As of 2013, it was unclear how much of a role birth asphyxia plays as a cause. It is unclear if the size of the placenta plays a role. As of 2015

it is evident that in advanced countries, most cases of cerebral palsy

in term or near-term neonates have explanations other than asphyxia.

Genetics

Autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.

About 2% of all CP cases are inherited, with glutamate decarboxylase-1 being one of the possible enzymes involved. Most inherited cases are autosomal recessive.

Early childhood

After birth, other causes include toxins, severe jaundice, lead poisoning, physical brain injury, stroke, abusive head trauma, incidents involving hypoxia to the brain (such as near drowning), and encephalitis or meningitis.

Others

Infections in the mother, even those not easily detected, can triple the risk of the child developing cerebral palsy . Infections of the fetal membranes known as chorioamnionitis increases the risk.

Intrauterine and neonatal insults (many of which are infectious) increase the risk.

It has been hypothesised that some cases of cerebral palsy are caused by the death in very early pregnancy of an identical twin.

Rh blood type incompatibility can cause the mother's immune system to attack the baby's red blood cells.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cerebral palsy has historically rested on the person's history and physical examination. A general movements assessment, which involves measuring movements that occur spontaneously among those less than four months of age, appears most accurate.

Children who are more severely affected are more likely to be noticed

and diagnosed earlier. Abnormal muscle tone, delayed motor development

and persistence of primitive reflexes are the main early symptoms of CP. Symptoms and diagnosis typically occur by the age of 2, although persons with milder forms of cerebral palsy may be over the age of 5, if not in adulthood, when finally diagnosed. Early diagnosis and intervention are seen as being a key part of managing cerebral palsy. It is a developmental disability.

Once a person is diagnosed with cerebral palsy, further diagnostic tests are optional. Neuroimaging with CT or MRI

is warranted when the cause of a person's cerebral palsy has not been

established. An MRI is preferred over CT, due to diagnostic yield and

safety. When abnormal, the neuroimaging study can suggest the timing of

the initial damage. The CT or MRI is also capable of revealing treatable

conditions, such as hydrocephalus, porencephaly, arteriovenous malformation, subdural hematomas and hygromas, and a vermian tumour

(which a few studies suggest are present 5–22% of the time).

Furthermore, an abnormal neuroimaging study indicates a high likelihood

of associated conditions, such as epilepsy and intellectual disability. There is a small risk associated with sedating children in facilitate a clear MRI.

The age when CP is diagnosed is important, but medical professionals disagree over the best age to make the diagnosis.

The earlier CP is diagnosed correctly, the better the opportunities are

to provide the child with physical and educational help, but there

might be a greater chance of confusing CP with another problem,

especially if the child is 18 months of age or younger. Infants may have temporary problems with muscle tone or control that can be confused with CP, which is permanent.

A metabolism disorder or tumors in the nervous system may appear to be

CP; metabolic disorders, in particular, can produce brain problems that

look like CP on an MRI. Disorders that deteriorate the white matter

in the brain and problems that cause spasms and weakness in the legs,

may be mistaken for CP if they first appear early in life. However, these disorders get worse over time, and CP does not (although it may change in character). In infancy it may not be possible to tell the difference between them. In the UK, not being able to sit independently by the age of 8 months is regarded as a clinical sign for further monitoring. Fragile X syndrome (a cause of autism and intellectual disability) and general intellectual disability must also be ruled out.

Cerebral palsy specialist John McLaughlin recommends waiting until the

child is 36 months of age before making a diagnosis, because by that

age, motor capacity is easier to assess.

Classification

CP

is classified by the types of motor impairment of the limbs or organs,

and by restrictions to the activities an affected person may perform. The Gross Motor Function Classification System-Expanded and Revised and the Manual Ability Classification System are used to describe mobility and manual dexterity in people with cerebral palsy, and recently the Communication Function Classification System, and the Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System have been proposed to describe those functions.

There are three main CP classifications by motor impairment: spastic,

ataxic, and athetoid/dyskinetic. Additionally, there is a mixed type

that shows a combination of features of the other types. These

classifications reflect the areas of the brain that are damaged.

Cerebral palsy is also classified according to the topographic distribution of muscle spasticity. This method classifies children as diplegic, (bilateral involvement with leg involvement greater than arm involvement), hemiplegic (unilateral involvement), or quadriplegic (bilateral involvement with arm involvement equal to or greater than leg involvement).

Spastic

Main article: Spastic cerebral palsy

Spastic

cerebral palsy, or cerebral palsy where spasticity (muscle tightness)

is the exclusive or almost exclusive impairment present, is by far the

most common type of overall cerebral palsy, occurring in upwards of 70%

of all cases. People with this type of CP are hypertonic and have what is essentially a neuromuscular mobility impairment (rather than hypotonia or paralysis) stemming from an upper motor neuron lesion in the brain as well as the corticospinal tract or the motor cortex. This damage impairs the ability of some nerve receptors in the spine to receive

gamma-Aminobutyric acid properly, leading to hypertonia in the muscles signaled by those damaged nerves.

[citation needed]

As compared to other types of CP, and especially as compared to

hypotonic or paralytic mobility disabilities, spastic CP is typically

more easily manageable by the person affected, and medical treatment can

be pursued on a multitude of orthopedic and neurological fronts throughout life. In any form of spastic CP, clonus of the affected limb(s) may sometimes result, as well as muscle spasms

resulting from the pain or stress of the tightness experienced. The

spasticity can and usually does lead to a very early onset of muscle

stress symptoms like arthritis and tendinitis, especially in ambulatory individuals in their mid-20s and early-30s. Physical therapy and occupational therapy regimens of assisted stretching, strengthening, functional tasks, or targeted physical activity and exercise

are usually the chief ways to keep spastic CP well-managed. If the

spasticity is too much for the person to handle, other remedies may be

considered, such as antispasmodic medications, botulinum toxin, baclofen, or even a neurosurgery known as a selective dorsal rhizotomy (which eliminates the spasticity by reducing the excitatory neural response in the nerves causing it).

[citation needed] Botulinum toxin is effective in decreasing spasticity.

It can help increase range of motion which could help mitigate CPs

effects on the growing bones of children. There is an improvement in

motor functions in the children and ability to walk.

Ataxic

Main article: Ataxic cerebral palsy

Ataxic cerebral palsy is observed in approximately 5-10% of all cases

of cerebral palsy, making it the least frequent form of cerebral palsy. Ataxic cerebral palsy is caused by damage to cerebellar structures. Because of the damage to the cerebellum,

which is essential for coordinating muscle movements and balance,

patients with ataxic cerebral palsy experience problems in coordination,

specifically in their arms, legs, and trunk. Ataxic cerebral palsy is

known to decrease muscle tone. The most common manifestation of ataxic cerebral palsy is intention (action) tremor,

which is especially apparent when carrying out precise movements, such

as tying shoe laces or writing with a pencil. This symptom gets

progressively worse as the movement persists, making the hand shake. As

the hand gets closer to accomplishing the intended task, the trembling

intensifies, which makes it even more difficult to complete.

Athetoid

Main article: Athetoid cerebral palsy

Athetoid cerebral palsy or dyskinetic cerebral palsy (sometimes abbreviated ADCP) is primarily associated with damage to the basal ganglia and the substantia nigra in the form of lesions that occur during brain development due to bilirubin encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. ADCP is characterized by both hypertonia and hypotonia, due to the affected individual's inability to control muscle tone. Clinical diagnosis of ADCP typically occurs within 18 months of birth and is primarily based upon motor function and neuroimaging techniques. Athetoid dyskinetic cerebral palsy is a non-spastic, extrapyramidal form of cerebral palsy. Dyskinetic cerebral palsy can be divided into two different groups; choreoathetoid and dystonic. Choreo-athetotic CP is characterized by involuntary movements most predominantly found in the face and extremities. Dystonic ADCP is characterized by slow, strong contractions, which may occur locally or encompass the whole body.

Mixed

Mixed

cerebral palsy has symptoms of athetoid, ataxic and spastic CP appearing

simultaneously, each to varying degrees, and both with and without

symptoms of each. Mixed CP is the most difficult to treat as it is

extremely heterogeneous and sometimes unpredictable in its symptoms and

development over the lifespan.

Prevention

Because the causes of CP are varied, a broad range of preventative interventions have been investigated.

Electronic fetal monitoring

has not helped to prevent CP, and in 2014 the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the Royal Australian and New Zealand

College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and the Society of

Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada have acknowledged that there

are no long-term benefits of electronic fetal monitoring. Prior to this, electronic fetal monitoring was widely used to prop up obstetric litigation.

In those at risk of an early delivery, magnesium sulphate appears to decrease the risk of cerebral palsy. It is unclear if it helps those who are born at term.

In those at high risk of preterm labor a review found that moderate to

severe CP was reduced by the administration of magnesium sulphate, and

that adverse effects on the babies from the magnesium sulphate were not

significant. Mothers who received magnesium sulphate could experience

side effects such as respiratory depression and nausea. However, guidelines for the use of magnesium sulfate in mothers at risk of preterm labour are not strongly adhered to. Caffeine is used to treat apnea of prematurity and reduces the risk of cerebral palsy in premature babies, but there are also concerns of long term negative effects. A moderate quality level of evidence indicates that giving women antibiotics

during preterm labor before her membranes have ruptured (water is not

yet not broken) may increase the risk of cerebral palsy for the child.

Additionally, for preterm babies for whom there is a chance of fetal

compromise, allowing the birth to proceed rather than trying to delay the birth may lead to an increased risk of cerebral palsy in the child. Corticosteroids are sometimes taken by pregnant women expecting a preterm birth to provide neuroprotection to their baby.

Taking corticosteroids during pregnancy is shown to have no significant

correlation with developing cerebral palsy in preterm births.

Cooling high-risk full-term babies shortly after birth may reduce disability, but this may only be useful for some forms of the brain damage that causes CP.

Management

Researchers are developing an electrical stimulation device specifically for children with cerebral palsy, who have foot drop, which causes tripping when walking.

Main article: Management of cerebral palsy

Over time, the approach to CP management has shifted away from narrow

attempts to fix individual physical problems – such as spasticity in a

particular limb – to making such treatments part of a larger goal of

maximizing the person's independence and community engagement.

:886

Much of childhood therapy is aimed at improving gait and walking.

Approximately 60% of people with CP are able to walk independently or

with aids at adulthood.

However, the evidence base for the effectiveness of intervention

programs reflecting the philosophy of independence has not yet caught

up: effective interventions for body structures and functions have a

strong evidence base, but evidence is lacking for effective

interventions targeted toward participation, environment, or personal

factors.

There is also no good evidence to show that an intervention that is

effective at the body-specific level will result in an improvement at

the activity level, or vice versa. Although such cross-over benefit might happen, not enough high-quality studies have been done to demonstrate it.

Because cerebral palsy has "varying severity and complexity" across the lifespan, it can be considered a collection of conditions for management purposes. A multidisciplinary approach for cerebral palsy management is recommended, focusing on "maximising individual function, choice and independence" in line with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health's goals. The team may include a paediatrician, a health visitor, a social worker, a physiotherapist, an orthotist, a speech and language therapist, an occupational therapist, a teacher specialising in helping children with visual impairment, an educational psychologist, an orthopaedic surgeon, a neurologist and a neurosurgeon.

Various forms of therapy are available to people living with

cerebral palsy as well as caregivers and parents. Treatment may include

one or more of the following: physical therapy; occupational therapy;

speech therapy; water therapy; drugs to control seizures, alleviate

pain, or relax muscle spasms (e.g. benzodiazepines); surgery to correct anatomical abnormalities or release tight muscles; braces and other orthotic devices; rolling walkers; and communication aids such as computers with attached voice synthesisers.

[citation needed]

A Cochrane review published in 2004 found a trend toward benefit of

speech and language therapy for children with cerebral palsy, but noted

the need for high quality research.

A 2013 systematic review found that many of the therapies used to treat

CP have no good evidence base; the treatments with the best evidence

are medications (anticonvulsants, botulinum toxin, bisphosphonates, diazepam), therapy (bimanual training, casting, constraint-induced movement therapy,

context-focused therapy, fitness training, goal-directed training, hip

surveillance, home programmes, occupational therapy after botulinum

toxin, pressure care) and surgery. Surgical intervention in CP children

mainly includes orthopaedic surgery and neurosurgery (selective dorsal rhizotomy).

Prognosis

CP is not a progressive disorder

(meaning the brain damage does not worsen), but the symptoms can become

more severe over time. A person with the disorder may improve somewhat

during childhood if he or she receives extensive care, but once bones

and musculature become more established, orthopedic surgery may be

required. People with CP can have varying degrees of cognitive impairment

or none whatsoever. The full intellectual potential of a child born

with CP is often not known until the child starts school. People with CP

are more likely to have learning disorders, but have normal intelligence. Intellectual level among people with CP varies from genius to intellectually disabled,

as it does in the general population, and experts have stated that it

is important not to underestimate the capabilities of a person with CP

and to give them every opportunity to learn.

The ability to live independently with CP varies widely,

depending partly on the severity of each person's impairment and partly

on the capability of each person to self-manage the logistics of life.

Some individuals with CP require personal assistant services for all activities of daily living.

Others only need assistance with certain activities, and still others

do not require any physical assistance. But regardless of the severity

of a person's physical impairment, a person's ability to live

independently often depends primarily on the person's capacity to manage

the physical realities of his or her life autonomously. In some cases,

people with CP recruit, hire, and manage a staff of personal care assistants

(PCAs). PCAs facilitate the independence of their employers by

assisting them with their daily personal needs in a way that allows them

to maintain control over their lives.

Puberty in young adults with cerebral palsy may be precocious or delayed. Delayed puberty is thought to be a consequence of nutritional deficiencies.

There is currently no evidence that CP affects fertility, although some

of the secondary symptoms have been shown to affect sexual desire and

performance. Adults with CP were less likely to get routine reproductive health screening as of 2005. Gynecological examinations may have to be performed under anesthesia due to spasticity, and equipment is often not accessible. Breast self-examination

may be difficult, so partners or carers may have to perform it. Women

with CP reported higher levels of spasticity and urinary incontinence

during menstruation in a study. Men with CP have higher levels of cryptorchidism at the age of 21.

CP can significantly reduce a person's life expectancy, depending

on the severity of their condition and the quality of care they

receive. 5-10% of children with CP die in childhood, particularly where seizures and intellectual disability also affect the child. The ability to ambulate, roll, and self-feed has been associated with increased life expectancy.

While there is a lot of variation in how CP affects people, it has been

found that "independent gross motor functional ability is a very strong

determinant of life expectancy". According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in 2014, 104 Australians died of cerebral palsy. The most common causes of death in CP are related to respiratory causes, but in middle age cardiovascular issues and neoplastic disorders become more prominent.

Self-care

For

many children with CP, parents are heavily involved in self-care

activities. Self-care activities, such as bathing, dressing, grooming,

can be difficult for children with CP as self-care depends primarily on

use of the upper limbs.

For those living with CP, impaired upper limb function affects almost

50% of children and is considered the main factor contributing to

decreased activity and participation. As the hands are used for many self-care tasks, sensory and motor impairments of the hands make daily self-care more difficult.

Motor impairments cause more problems than sensory impairments. The most common impairment is that of finger dexterity, which is the ability to manipulate small objects with the fingers. Compared to other disabilities, people with cerebral palsy generally need more help in performing daily tasks.

Occupational therapists are healthcare professionals that help

individuals with disabilities gain or regain their independence through

the use of meaningful activities.

Productivity

The

effects of sensory, motor and cognitive impairments affect self-care

occupations in children with CP and productivity occupations.

Productivity can include, but is not limited to, school, work, household

chores or contributing to the community.

Play is included as a productive occupation as it is often the primary activity for children. If play becomes difficult due to a disability, like CP, this can cause problems for the child. These difficulties can affect a child's self-esteem.

In addition, the sensory and motor problems experienced by children

with CP affect how the child interacts with their surroundings,

including the environment and other people.

Not only do physical limitations affect a child's ability to play, the

limitations perceived by the child's caregivers and playmates also

affect the child's play activities. Some children with disabilities spend more time playing by themselves. When a disability prevents a child from playing, there may be social, emotional and psychological problems, which can lead to increased dependence on others, less motivation, and poor social skills.

In school, students are asked to complete many tasks and

activities, many of which involve handwriting. Many children with CP

have the capacity to learn and write in the school environment.

However, students with CP may find it difficult to keep up with the

handwriting demands of school and their writing may be difficult to

read. In addition, writing may take longer and require greater effort on the student's part.

Factors linked to handwriting include postural stability, sensory and

perceptual abilities of the hand, and writing tool pressure.

Speech impairments may be seen in children with CP depending on the severity of brain damage.

Communication in a school setting is important because communicating

with peers and teachers is very much a part of the "school experience"

and enhances social interaction. Problems with language or motor

dysfunction can lead to underestimating a student's intelligence.

In summary, children with CP may experience difficulties in school,

such as difficulty with handwriting, carrying out school activities,

communicating verbally and interacting socially.

Leisure

Leisure

activities can have several positive effects on physical health, mental

health, life satisfaction and psychological growth for people with

physical disabilities like CP.

Common benefits identified are stress reduction, development of coping

skills, companionship, enjoyment, relaxation and a positive effect on

life satisfaction. In addition, for children with CP, leisure appears to enhance adjustment to living with a disability.

Leisure can be divided into structured (formal) and unstructured (informal) activities. Children and teens with CP engage in less habitual physical activity than their peers. Children with CP primarily engage in physical activity through therapies aimed at managing their CP, or through organized sport for people with disabilities. It is difficult to sustain behavioural change in terms of increasing physical activity of children with CP.

Gender, manual dexterity, the child's preferences, cognitive impairment

and epilepsy were found to affect children's leisure activities, with

manual dexterity associated with more leisure activity.

Although leisure is important for children with CP, they may have

difficulties carrying out leisure activities due to social and physical

barriers.

Children with cerebral palsy may face challenges when it comes to

participating in sports. This comes with being discouraged from

physical activity because of these perceived limitations imposed by

their medical condition.

Participation and barriers

Participation is involvement in life situations and everyday activities.

Participation includes self-care, productivity, and leisure. In fact,

communication, mobility, education, home life, leisure and social

relationships require participation, and indicate the extent to which

children function in their environment. Barriers can exist on three levels: micro, meso and macro. First, the barriers at the micro level involve the person.

Barriers at the micro level include the child's physical limitations

(motor, sensory and cognitive impairments) or their subjective feelings

regarding their ability to participate.

For example, the child may not participate in group activities due to

lack of confidence. Second, barriers at the meso level include the

family and community. These may include negative attitudes of people toward disability or lack of support within the family or in the community.

One of the main reasons for this limited support appears to be the

result of a lack of awareness and knowledge regarding the child's

ability to engage in activities despite his or her disability.

Third, barriers at the macro level incorporate the systems and policies

that are not in place or hinder children with CP. These may be

environmental barriers to participation such as architectural barriers,

lack of relevant assistive technology and transportation difficulties

due to limited wheelchair access or public transit that can accommodate

children with CP.

For example, a building without an elevator can prevent the child from accessing higher floors.

A 2013 review stated that outcomes for adults with cerebral palsy

without intellectual disability in the 2000s were that "60-80%

completed high school, 14-25% completed college, up to 61% were living

independently in the community, 25-55% were competitively employed, and

14-28% were involved in long term relationships with partners or had

established families".

Adults with cerebral palsy may not seek physical therapy due to

transport issues, financial restrictions and practitioners not feeling

like they know enough about cerebral palsy to take people with CP on as

clients.

A study in young adults

(18-34) on transitioning to adulthood found that their concerns were

physical health care and understanding their bodies, being able to

navigate and use services and supports successfully, and dealing with

prejudices. A feeling of being "thrust into adulthood" was common in the

study.

Aging

Children

with CP may not successfully transition into using adult services

because they are not referred to one upon turning 18, and may decrease

their use of services.

Because children with cerebral palsy are often told that it is a

non-progressive disease, they may be unprepared for the greater effects

of the aging process as they head into their 30s. Young adults with cerebral palsy experience problems with aging that able-bodied adults experience "much later in life".

:42 25% or more adults with cerebral palsy who can walk experience increasing difficulties walking with age. Chronic disease risk, such as obesity, is also higher among adults with cerebral palsy than the general population. Common problems include increased pain, reduced flexibility, increased spasms and contractures, post-impairment syndrome, and increasing problems with balance. Increased fatigue is also a problem. When adulthood and cerebral palsy is discussed, as of 2011, it is not discussed in terms of the different stages of adulthood.

Like they did in childhood, adults with cerebral palsy experience

psychosocial issues related to their CP, chiefly the need for social

support, self-acceptance, and acceptance by others. Workplace

accommodations may be needed to enhance continued employment for adults

with CP as they age. Rehabilitation or social programs that include Salutogenesis may improve the coping potential of adults with CP as they age.

Epidemiology

Cerebral palsy occurs in about 2.1 per 1000 live births. In those born at term rates are lower at 1 per 1000 live births. Rates appear to be similar in both the developing and developed world. Within a population it may occur more often in poorer people. The rate is higher in males than in females; in Europe it is 1.3 times more common in males.

Variances in reported rates of incidence or prevalence across different

geographical areas in industrialised countries are thought to be caused

primarily by discrepancies in the criteria used for inclusion and

exclusion. When such discrepancies are accounted for in comparing two or

more registers of patients with cerebral palsy (for example, the extent

to which children with mild cerebral palsy are included), prevalence

rates converge toward the average rate of 2:1000.

There was a "moderate, but significant" rise in the prevalence of

CP between the 1970s and 1990s. This is thought to be due to a rise in low birth weight

of infants and the increased survival rate of these infants. The

increased survival rate of infants with CP in the 1970s and 80s may be

indirectly due to the disability rights movement challenging perspectives around the worth of infants with disability, as well as the Baby Doe Law.

As of 2005, advances in care of pregnant mothers and their babies

has not resulted in a noticeable decrease in CP. This is generally

attributed to medical advances in areas related to the care of premature

babies (which results in a greater survival rate). Only the

introduction of quality medical care to locations with

less-than-adequate medical care has shown any decreases. The incidence

of CP increases with premature or very low-weight babies regardless of

the quality of care. As of 2016,

there is a suggestion that both incidence and severity are slightly

decreasing - more research is needed to find out if this is significant,

and if so, which interventions are effective.

Prevalence

of cerebral palsy is best calculated around the school entry age of

about 6 years, the prevalence in the U.S. is estimated to be 2.4 out of

1000 children.

History

Cerebral

palsy has affected humans since antiquity. A decorated grave marker

dating from around the 15th to 14th century BCE shows a figure with one

small leg and using a crutch, possibly due to cerebral palsy. The oldest

likely physical evidence of the condition comes from the mummy of Siptah, an Egyptian Pharaoh

who ruled from about 1196 to 1190 BCE and died at about 20 years of

age. The presence of cerebral palsy has been suspected due to his

deformed foot and hands.

The medical literature of the ancient Greeks discusses paralysis and weakness of the arms and legs; the modern word

palsy comes from the Ancient Greek words

παράλυση or

πάρεση, meaning paralysis or paresis respectively. The works of the school of Hippocrates (460–c. 370 BCE), and the manuscript

On the Sacred Disease

in particular, describe a group of problems that matches up very well

with the modern understanding of cerebral palsy. The Roman Emperor Claudius

(10 BCE–54 CE) is suspected of having CP, as historical records

describe him as having several physical problems in line with the

condition. Medical historians have begun to suspect and find depictions

of CP in much later art. Several paintings from the 16th century and

later show individuals with problems consistent with it, such as Jusepe de Ribera's 1642 painting

The Clubfoot.

The modern understanding of CP as resulting from problems within

the brain began in the early decades of the 1800s with a number of

publications on brain abnormalities by Johann Christian Reil, Claude François Lallemand and Philippe Pinel. Later physicians used this research to connect problems in the brain with specific symptoms. The English surgeon William John Little

(1810–1894) was the first person to study CP extensively. In his

doctoral thesis he stated that CP was a result of a problem around the

time of birth. He later identified a difficult delivery, a preterm birth and perinatal asphyxia in particular as risk factors. The spastic diplegia form of CP came to be known as Little's disease. At around this time, a German surgeon was also working on cerebral palsy, and distinguished it from polio. In the 1880s British neurologist William Gowers

built on Little's work by linking paralysis in newborns to difficult

births. He named the problem "birth palsy" and classified birth palsies

into two types: peripheral and cerebral.

Working in Pennsylvania in the 1880s, Canadian-born physician William Osler

(1849–1919) reviewed dozens of CP cases to further classify the

disorders by the site of the problems on the body and by the underlying

cause. Osler made further observations tying problems around the time of

delivery with CP, and concluded that problems causing bleeding inside

the brain were likely the root cause. Osler also suspected

polioencephalitis as an infectious cause. Through the 1890s, scientists

commonly confused CP with polio.

Before moving to psychiatry, Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud

(1856–1939) made further refinements to the classification of the

disorder. He produced the system still being used today. Freud's system

divides the causes of the disorder into problems present at birth,

problems that develop during birth, and problems after birth. Freud also

made a rough correlation between the location of the problem inside the

brain and the location of the affected limbs on the body, and

documented the many kinds of movement disorders.

In the early 20th century, the attention of the medical community

generally turned away from CP until orthopedic surgeon Winthrop Phelps

became the first physician to treat the disorder. He viewed CP from a musculoskeletal

perspective instead of a neurological one. Phelps developed surgical

techniques for operating on the muscles to address issues such as

spasticity and muscle rigidity. Hungarian physical rehabilitation practitioner András Pető

developed a system to teach children with CP how to walk and perform

other basic movements. Pető's system became the foundation for conductive education,

widely used for children with CP today. Through the remaining decades,

physical therapy for CP has evolved, and has become a core component of

the CP management program.

In 1997, Robert Palisano

et al. introduced the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) as an improvement over the previous rough assessment of limitation as either mild, moderate or severe.

The GMFCS grades limitation based on observed proficiency in specific

basic mobility skills such as sitting, standing and walking, and takes

into account the level of dependency on aids such as wheelchairs or

walkers. The GMFCS was further revised and expanded in 2007.